How can we shape the health ecosystem of the future? The enormity of the challenges facing innovation and digital transformation in healthcare cannot be overstated. While medical care and wellness have advanced rapidly in the past 100 years, they’ve still struggled to fully benefit from advances in technology.

Healthcare has multitudes of user groups, stakeholders, and other players. It’s a complex landscape of providers, payers, patients, products, and services. Innovation in healthcare is further complicated by issues such as data fragmentation, bias in machine learning, and accessibility challenges in digital health. This two-part series explores these challenges and how they can be solved by design. Aspirationally, it also considers: how might designers use technology to put patients at the center of healthcare, so that outcomes are improved and costs are reduced?

Recent studies suggest medical errors (specifically, errors in treatment) have become the third leading cause of death in the United States. The best technology can hinder care by providing too much information, or by displaying important information in a confusing way. Just five years ago, a young cancer patient lost her life because nurses were unable to decipher the software used to support her care. Overdoses because of byzantine software user interfaces are cruelly all too common, as the patient who received 38 times their usual dose of medication can attest. As much as effective digital tools can provide access to life-saving information, they can also hinder successful administration of care because of unusable experiences or a lack of consideration for patient/provider inclusivity.

Information overload isn’t limited to visuals, either. 85% to 95% of alarms that go off in an inpatient hospital setting require no intervention by a medical professional. Alarm fatigue and other alarm issues are so pervasive that they have made the ECRI Top 10 Health Technology Hazard list since 2007, and alarm fatigue was a 2014 Joint Commission National Patient Safety Goal. Again, this is a challenge that can potentially be solved through design and advancements in technology. However, it must be considered which alarms are meaningful for each patient/care situation, and how to present them in an accessible, contextualized, and inclusive manner.

Inclusivity in Digital Health

Even when innovative digital tools and services benefit patients, they are only as good as the people who build them. Diversity and inclusion must be considered as part of the design and development of an effective holistic healthcare system. Inclusive design is beginning to make positive strides in healthcare, though more is needed. Among other things, on the patient side this means ensuring:

- equal access to care.

- equal opportunity to have the best possible outcomes.

- and equal treatment and respect.

This is regardless of background, race, personal experience, sexual orientation, gender, or any other factor. With medical training, we need to support this patient experience and inclusivity. In addition, all medical staff should be guaranteed equal access to training and advancement, as well as equal treatment in the workplace. These same considerations should apply across patient experiences, staff experiences, community involvement, and inter-company relations.

To support this outcome, diversity and inclusion have rightfully come to the forefront of healthcare in recent years. In 2016, Harvard Medical students petitioned the university president to increase diversity and inclusivity within the student and faculty. Earlier this year, Time’s Up announced “a new affiliate that aims to tackle discrimination, harassment, and inequality across the health care industry”.

On the patient side, the National Institute of Health passed guidelines in 2017 to promote inclusion of all ages in research studies. This legislation was targeted towards combating insufficient research being performed on patients because conditions that correlate with age were being excluded from studies. Previously, one-quarter of research studies excluded patients 65 and over, even if the study was intended to look at treating diseases in that population.

The Hidden Bias in Healthcare

Knowing these systemic issues, bias should be top of mind when using machine learning and data for medical care. Designers and engineers alike should be armed with the knowledge needed to shape inclusive algorithms that enable this technology. Therefore, it raises ethical concerns when leading minds in healthcare are proud to build their biases into machine learning algorithms like Watson Health:

We are not at all hesitant about inserting our bias, because I think our bias is based on the next best thing to prospective randomized trials, which is having a vast amount of experience. - Dr. Andrew Seidman

Watson’s bias towards the patient population it was trained for has slowed adoption in other countries. Denmark dropped use of Watson after finding doctors only agreed with it roughly a third of the time. These, too, are the kinds of issues that could have been uncovered at earlier stages with the right combination of understanding the interactions, people, processes, and touchpoints working to create such outcomes. This bias is not an isolated occurrence. AI and machine learning models are largely trained on Caucasian men from affluent neighborhoods. When those results are extrapolated to the full diversity of the patient spectrum, everyone else falls through the cracks. For example:

- The mortality rates from heart disease, breast cancer, and stroke decreased between the years 1990 to 2005, but the gap between black and white mortality rates actually increased. 1

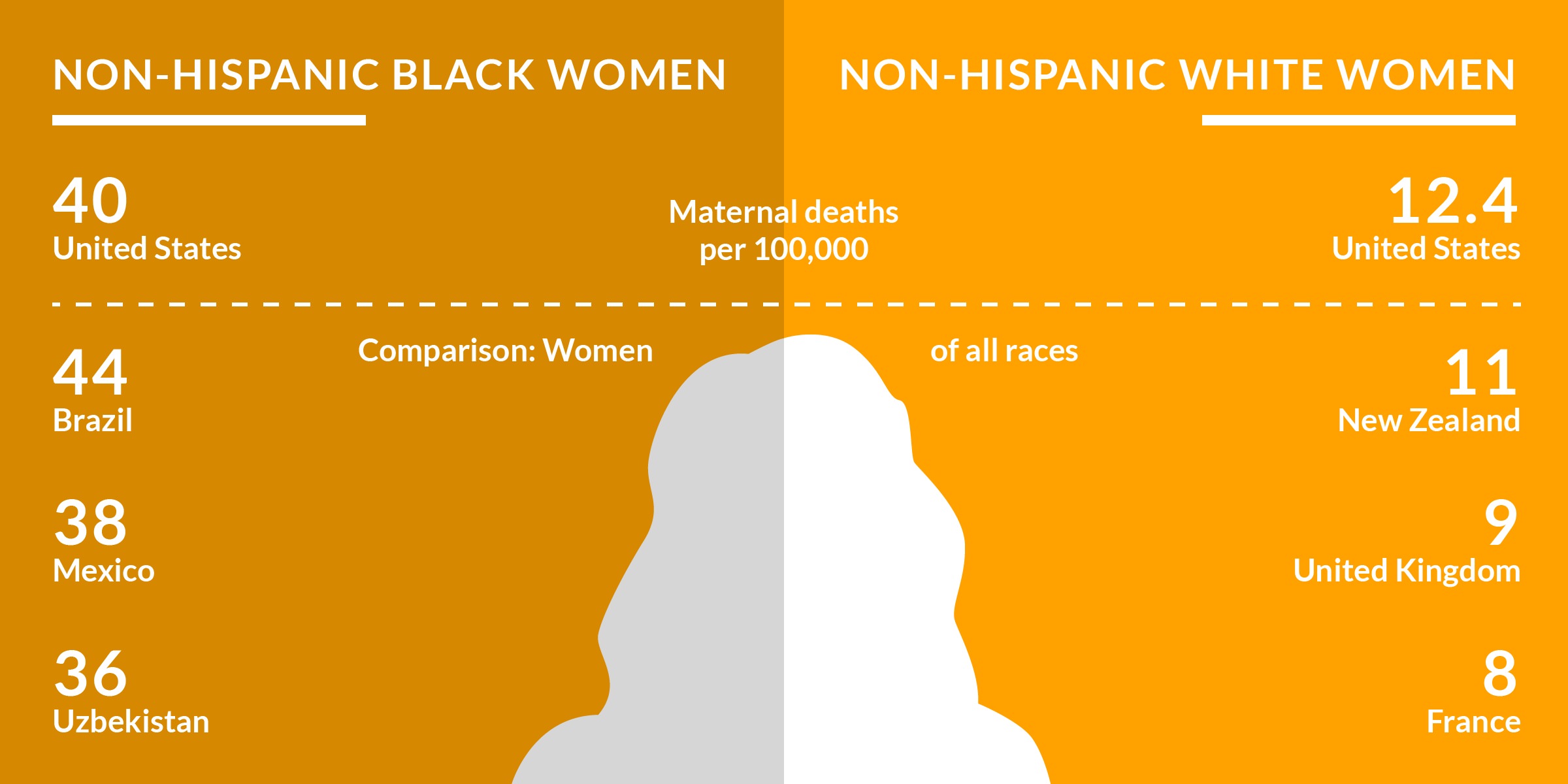

- The mortality rate for African-American infants is almost 2.5 times greater than it is for white infants. In addition, black mothers die of pregnancy-related complications at three to four times the rate of white women. 2

- Hispanic and African-American youth are substantially more likely to die of diabetes than white youth.

- In some parts of the country, Native American life expectancy is 20 years shorter than the average. The federal government spends $1,297 per Native American on healthcare, compared to $6,973 per federal prison inmate.

- Among transgender people, “29 percent said a doctor or other health care provider refused to see them because of their actual or perceived gender identity.”

- Lesbian and bisexual women have higher risk of breast cancer, and may have a higher risk of cervical cancer. There are many other healthcare concerns and care gaps for LGBTQ groups.

- Cantina previously referenced the vast portions of America falling through the healthcare professional shortage gaps. For further reading into care gaps in rural and underserved populations, the Health and Place in America report is a deep dive into the relationship between our communities and our health.

In fact, “even when controlling for access-related factors, such as patients’ insurance status and income, some racial and ethnic minority groups are still more likely to receive lower-quality health care.” What’s transpiring in healthcare is that technology isn’t necessarily helping at-risk groups receive better care. In fact, in many cases, it is widening the gap between the health-wealthy and the health-poor.

Modern Design Frameworks for Modern Medicine

There is a systemic diversity issue in healthcare. From the medical training programs that are producing tomorrow’s doctors, to the digital products and services being used to transform healthcare, designers have a responsibility to help improve outcomes and reduce care gaps for everyone. They also have a responsibility to shape the processes that enable healthcare experiences for patients and healthcare providers alike.

Systemic challenges require systemic change. Technology only gives us tools, and while they may assist in improving outcomes, they can’t be relied upon to fix the entire patient experience. Whether designed or not, there are vast, complicated systems that grow and evolve around digital products. These systems are exactly what service design is intended to shape. Change must happen at the patient level with preventative care, support networks, consumer-driven health, and chronic condition management. Further, change must happen at the organizational level, with value-based care, interoperability between health systems and technology, and training to mitigate bias with staff.

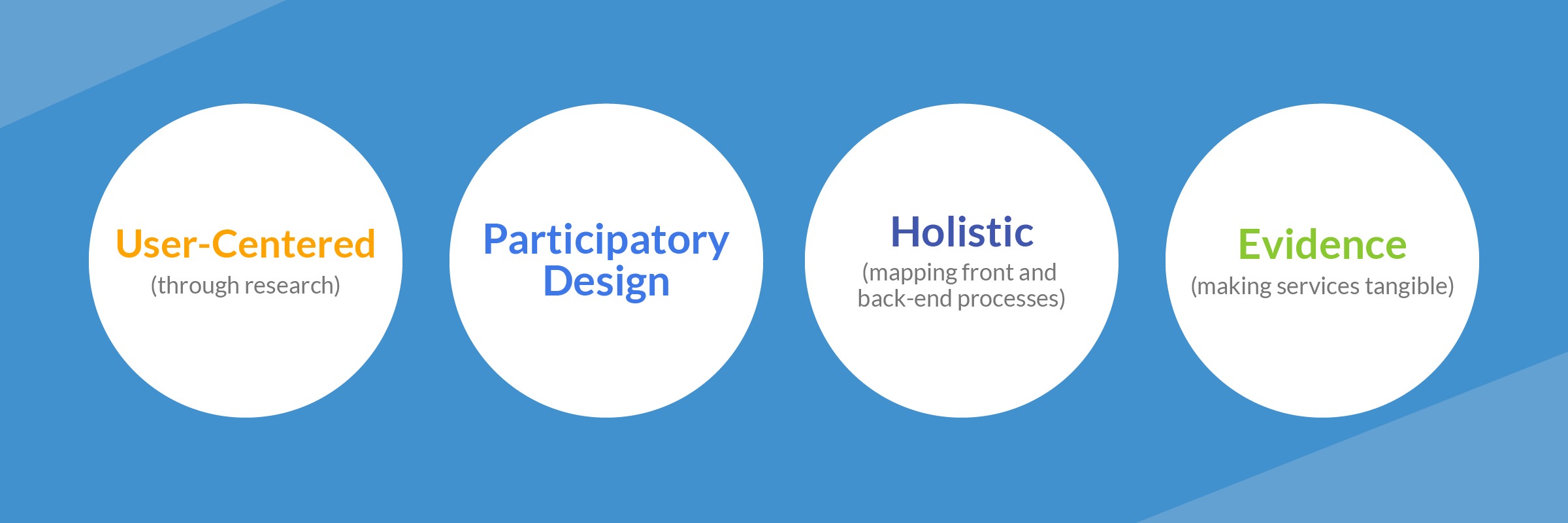

Digital transformation asks for innovation, and true innovation is a continuous, iterative process. It is not overhauling outdated systems once every ten years. Nor is it converting paper forms to digital PDFs. Healthcare needs “a user-centric approach that includes service providers, end-users and stakeholders in the design process.” Knowing all this as designers, how can an action plan to transform the patient journey be created? Digital transformation is not enough. The challenges facing healthcare require more. What’s needed is:

Pioneers in this space like Docent Health are applying service design and experience strategy to empower healthcare organizations to change for the better. Service design differs from traditional UX methods in its focus on multi-user perspectives, channel-agnosticism, and the connections it makes between experiences and the processes that make them possible. Experience strategy supports service design through research and focusing organizations on principles for solving experience challenges. This is all enabled through a deep understanding of patients, staff, and supporting players, as well as the organizations and systems around them.

With service design, designers can look at the entire journey for everyone (patients, staff, and supporting players) from start to finish. Experience strategy gives designers tools to research and study organizations and participants from their perspective. Everyone from clinicians, to pharmacists, to medical equipment and technology managers can feel empowered to make the right choices for patient care and wellness. Patients and staff alike can feel supported and enabled by the system, and not limited by it.

Service design focuses on a holistic and inclusive view. Through co-creation, designed evidence, and maintaining a user-centered mindset, designers can map out complex systems and better understand how to improve them. The second article in this series focuses on principles of service design at Cantina, and how they can be applied to inclusivity in digital health, and success stories from the field.

The first step in designing inclusive services is crafting an experience strategy. If you’re interested in learning how strategic design can enable digital transformation in healthcare, check out Cantina’s Experience Strategy Method Cards. If you’d like to learn more about applying service design principles and bringing experience strategy to your organization, contact us today.

-

Commonwealthfund.org. (2019). [In Focus: Reducing Racial Disparities in Health Care by Confronting Racism Commonwealth Fund.](https://www.commonwealthfund.org/publications/newsletter-article/2018/sep/focus-reducing-racial-disparities-health-care-confronting) -

Harvard Public Health Magazine. (2019). America is Failing its Black Mothers. ↩