Chatbots contain multitudes.

At Cantina, we’re really big fans of the Jobs To Be Done framework. Invented by Harvard Business School Professor Clayton Christensen—the “disruption” guy—it aims to understand consumer choices at the moment of purchase based on what the buyer hopes to achieve. In short, we expect things we buy to do a job for us.

As touched on earlier, chatbot technology can solve a job to be done. That means to understand what the user really needs, we need to write Job Stories.

Unlike the bias-loaded hot potatoes we call Personas, Job Stories embrace context and causality to really dig into motivations: When this event happens, my motivation drives me to make this decision to get this outcome.

The big revelation of the project was that, just like a person, a chatbot’s behavior shifts depending on the kind of task you ask it to do. Each chatbot prompt—the bit of text that helps the user get what they need—is effectively its own self-contained Job Story. Mapping voice and tone to these prompts goes a long way toward making the chatbot resonate with the user.

Think about the concierge metaphor again. When a concierge is asked something they have knowledge about, their answer is probably going to sound friendly, yet authoritative: “Yes, I can help you find that museum—it’s over here.”

When asked a question they’re not familiar with, the tone might shift to be more apologetic, but not to the point of groveling: “I’m sorry, I’m not familiar with that dish, but I can check the local restaurants for you.”

When asked for help by someone exasperated or in a moment of crisis, a concierge might respond in a way that acknowledges the elevated emotional state without feeding back into it: “The bandages are over here. Follow me.”

Work on establishing the overall voice and tone first when developing the chatbot personality. This is a great opportunity to put your existing brand guidelines through their paces. Or if none exist yet, establish some. The chatbot should feel like an extension of the brand and not vice-versa.

Come up with a set list of actions that correspond to the design goals of the chatbot. Treat the general personality as the baseline, and tweak as needed. If a chatbot’s core personality is excited, you may want to temper it in situations where that could scare someone off.

You’ll also want to consider the emotional context of the person arriving at that situation. How do you think they’ll feel beforehand? How do you want them to feel afterwards?

The best way to determine these situations and outcomes? Testing. Lots and lots of testing.

Chatbots sound like people, until they don’t.

A chatbot interface is text—written or spoken. The users interacts by typing or saying queries or commands and seeing how the chatbot responds. With a well-crafted chatbot these responses feel natural and logical, and wind up approximating a conversation.

Unfortunately, chatbots simply aren’t that great at keeping up. They can’t sense emotion. They don’t understand abstract language, sarcasm, idioms, and the other quirks of language that linguists like to write research papers about. Natural Language Processing and sentiment analysis can help some, but in our experience, relying on technology to cheat things humans are unconsciously sensitive to rarely works reliably.

Dialing in responses takes a surprisingly large amount of work. The next time you overhear people talking, pay attention. Not to what they’re talking about, but how they go about getting to a point. Conversations are fluid—they shift from topic to topic on the fly, include references to previous points, blend in jokes and metaphor, and can end as abruptly as they start.

The best way to deal with these linguistic shortcomings is to be honest and upfront that the chatbot isn’t human. Setting expectations neatly sidesteps the Uncanny Valley problem and eliminates the impossible task of trying to build something that simultaneously passes the Turing Test and satisfies stakeholder requirements.

Another good trick to keeping things feeling natural is to never let the chatbot’s dialogue reach a hard stop. Always offer at least one obvious action to take. Facebook Messenger, for example, can display quick responses showing which actions are available to move the conversation forward. Leverage these kinds of affordances as much as possible, if the platform offers them.

Chatbots need a writer to give them life.

When done well, websites are great at telling users where they are on the site: Main navigation can quickly show big-picture topics the site covers. A logo links back to the homepage. Breadcrumb links show where a user has been, and a footer can usher users to another section when they’re done reading.

Chatbots lack the navigational redundancies and affordances of a typical website. Errors are very problematic. While people browsing a website may forgive small omissions, people quickly blame chatbot misinterpretations on a “dumb robot.” This, combined with the lack of an obvious way to back out of a dead end can make abandonment rates high.

How do you combat this? With writing. With a chatbot, the writing is the user experience. Every word must be considered and tested—not as a standalone phrase but how it fits into the rest of the conversational flow.

To do this bring in a specialist: a writer. Generally speaking, the chatbot developer is really good at code. The marketer promoting the chatbot is really good at showcasing the brand. The designer will give the chatbot a face. Writers are really great at giving life to characters. And chatbots are characters.

Interacting with a chatbot is a facsimile of interacting with a person. The user will project unconscious expectations of human-to-human conversation onto the experience. A good writer will be mindful of this kind of nuance to help address those expectations and keep things moving along smoothly.

It’s this nuance that fills in the gaps to make the interaction seem “real”. It doesn’t have to be perfect, it just needs to make the chatbot seem alive enough that we’re willing to overlook the areas where they’re weakest.

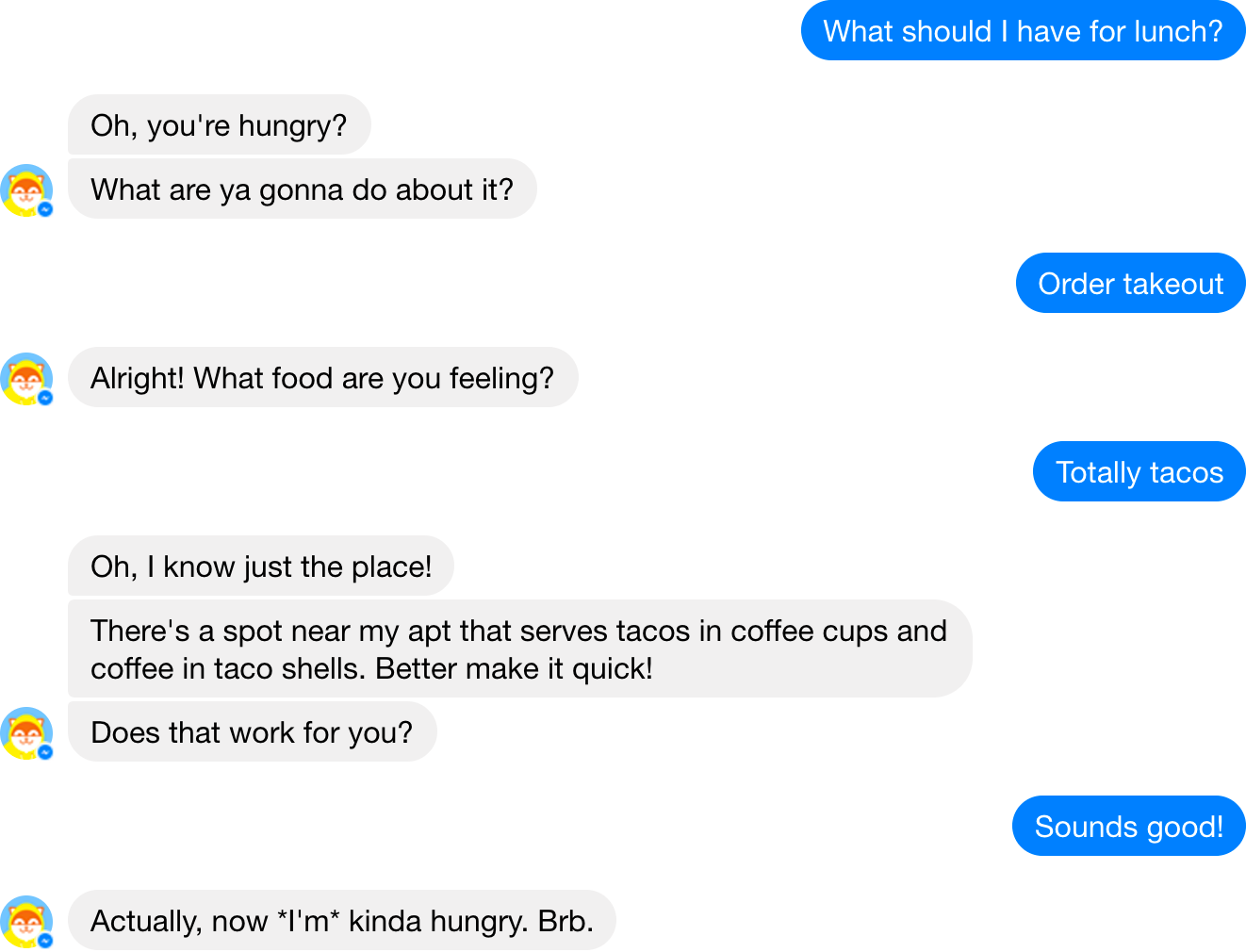

Poncho, a chatbot that tells you the weather, has a great example of this when you ask it about food. It’s a common thing people talk about and although it’s not in the scope of the app’s main functionality, its responses are playful enough to keep you engaged.

Human: What should I have for lunch?

Poncho: Oh, you're hungry? What are ya gonna do about it?

Human: Order takeout

Poncho: Alright! What food are you feeling?

Human: Totally tacos

Poncho: Oh, I know just the place! There's a spot near my apt that serves tacos in coffee cups and coffee in taco shells. Better make it quick! Does that work for you?

Human: Sounds good!

Poncho: Actually, now I'm kinda hungry. Brb.

If you pay careful attention to the conversation, you’ll note that it is constructed in such a way where the answers the user supplies don’t technically matter. It is carefully taking open-ended responses and guiding the conversation back on track. Clever!

Once testing has given you the confidence that the chatbot really is satisfying the job you’ve tasked it with doing, utilizing the discoveries outlined earlier can create users who will be excited to engage with a chatbot—possibility even repeatedly!

If you have an existing chatbot project, or are thinking of starting one and would like help with the process, we would love the opportunity to help. Get in contact today!