In the United States, we produce 30% of global waste despite having 4% of the world’s population, and more than 90% of our recyclable plastic ends up in landfills. The economic impact of China’s ban on buying foreign recyclables with the National Sword campaign has brought attention to the need for more national recycling infrastructure, but the focus remains on waste management and resists challenging the status quo of how much waste we produce in the first place.

These kinds of environmental statistics can feel overwhelming and beyond our grasp as individuals - with such a broad issue, who is to blame and who can really have an impact on changing the system? From a design perspective, I wanted to figure out how we can understand the impact of the waste we produce as something tangible and accessible. To do so, I had to go beyond asking people whether they care about environmental issues and waste on a broad level and instead zoom in on how sustainable values are implemented on a daily basis.

I had to go beyond asking people whether they care about environmental issues and waste on a broad level and instead zoom in on how sustainable values are implemented on a daily basis.

With this goal, I ran a weeklong research project in order to identify opportunities to leverage behavioral science and habit models to help individuals reduce the daily waste they create. As someone who’s passionate about environmental justice and sustainability, I’m especially interested in movements like Zero Waste that urge people to think about the material stuff they consume and throw away as another component of health and wellness. Could it be possible to use existing frameworks of how healthy habits are developed and maintained to help people reduce the waste they create?

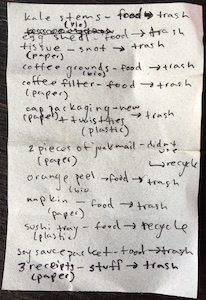

Using a series of diary studies, I was able to dive deeper into some of the contexts in which sustainable values and practices clash with day-to-day obstacles and motivations. I asked six participants to write down every piece of trash they threw away during the course of a single day including the item’s purpose, the materials of which it was composed, and whether it ended up in the compost, recycling, or landfill. After documenting their day, they reflected a bit on how the process made them feel and whether their behavior or relationship with their waste changed at all. Besides allowing me to put some distance between myself as a user and myself as a designer, these studies revealed a few key wants and needs that had the potential to either work with or against reducing waste for the sake of sustainability.

|

|

|

One key need I discovered was the ability to break down a broad goal of reducing waste into tangible steps and understand the direct impacts of those actions. Participants identified a personal disconnect between their own individual routines and crisis-based environmental issues they heard about on the news, and weren’t sure where to start in terms of living more sustainably. In comparison to other daily challenges and concerns, the long-term effects of climate change feel far away even if we acknowledge the human causes. As one participant put it, “I have an effect on environmental issues but they don’t affect me.” With trash in particular, participants felt that movements like Zero Waste framed efforts at waste reduction as failures if they couldn’t immediately stop throwing anything away. There is so much competing information out there about the relative impacts of different kinds of waste and waste management that they weren’t sure which lifestyle changes were worth the effort.

When I asked the participants to reflect on how they defined the outcomes of other habits that reflect their values as being worth the extra effort, I found that most of them relied on external educational sources like news articles, scientific studies, and sociopolitical movements. When asking about waste, I heard a lot of variants on “I recycle because it’s the norm.” What was most interesting to me was a comment from one participant feeling guilty for defying that norm - “I was more self-conscious about having to write things down, especially when I didn’t have the opportunity to recycle everything that I used.”

That “self-conscious” aspect of the task I had set out revealed a social element to turning a goal into behavior and habits. By introducing this challenge to the six participants and connecting it to their reflections on how and why they turn their values into action, a lot of the response centered around:

- Need to be held accountable

- Desire for recognition of their individual impact,

- Shame around how certain actions contradict the values they wish to communicate to others.

A surprising piece of these findings was how much more likely people were to behave in a way that reflected specific values when their behavior had an effect on personal relationships, and how individual production of waste didn’t seem to be a part of that pattern. A key shift in the messaging of recent environmental movements has been the growing focus on the intersectional impacts of climate change on humans - undermining the dichotomy of nature and culture - and it was interesting to think about how this emerging understanding of environmental justice could activate relationship-driven motivations for reducing waste.

Framing these findings as problem statements helped me get a clear grasp of how this initial research could reveal an opportunity for design to have a lasting impact.

How we might help:

- Users break down their broad goal of reducing personal waste into tangible steps and outcomes so that they can understand the impact of their progress?

- Activate a user’s desire for their individual impact to be recognized so that they can communicate their values to the people around them?

- Figure out steps to reduce waste that fit into their lifestyles so that they can afford to make decisions that prioritize sustainability?

To learn about how sustainable values translate into behavior, it was crucial to identify real life, day-to-day obstacles and motivations rather than just asking if people care about the environment or want to save the world. It opens up the possibilities for design solutions to fit people’s specific needs and lifestyles rather than disrupting them, and for those solutions to contribute to creating new norms of how we relate to the trash we produce.

If you’re interested in learning more about Madeleine’s research or have a similar project you’d like to talk about, please send us an email.