With the advent of the mobile age has come an unprecedented opportunity to help those in disadvantaged communities.

Independent apps like GoFundMe, Share the Meal, and Givelify, as well as large tech companies like Facebook and Apple, have made giving to charity more accessible and easy to use than ever before. These advances come with a set of unique challenges to designers interested in this space:

- What functions should we prioritize to best help those in need?

- How can our product stand out?

- How can we design the experience to motivate people to donate?

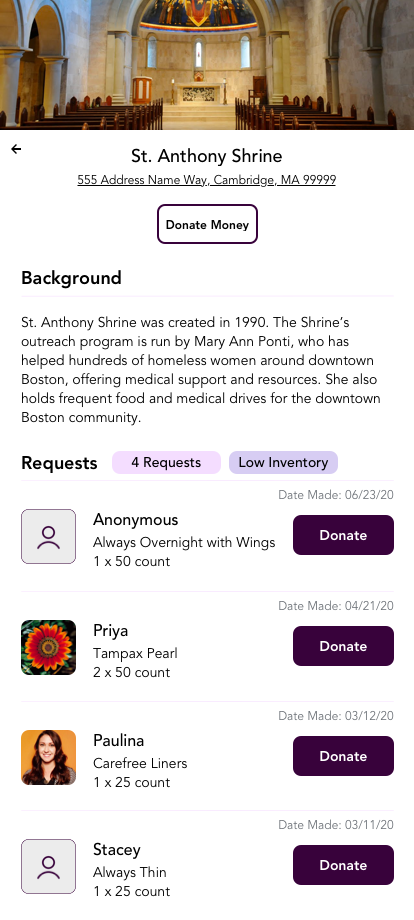

Recently, I worked on a project that focused on providing an easy donation experience for menstrual products. I designed a mobile app that allows individual low-income women to request products and others to donate them. A part of this process is showing personal details about a requester, such as a face and a name. This idea posed a big challenge: balancing the project goal of driving donations with protecting the privacy of key users.

As the product owner, my goal was to drive donations and the research was in favor of sharing personal details. But also as the designer, I wanted to put my users’ needs first. The logical compromise was to make that feature optional; users can decide if they would like to reveal those details about themselves. However, that also brought up an interesting question about biases:

- Will users who choose to show their face and name receive more donations than those who don’t?

- Are certain details more influential over others?

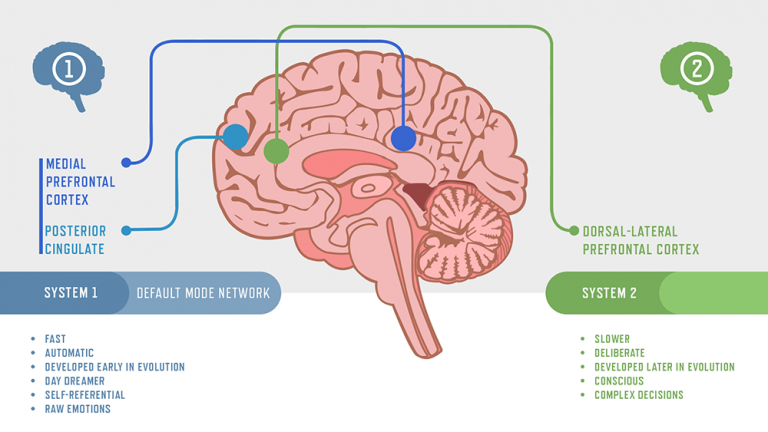

Research has suggested that eliciting an emotional response in someone may promote a stronger desire in them to help those in need. As humans, we tend to make emotional decisions rather than rational ones. Notable psychologist Daniel Kahneman claims that the brain can be separated into two systems. System 1 is fast, emotional, and unconscious while System 2 is slow, logical, and conscious. Kahneman suggests that while we like to think that we are using System 2 to make deliberate choices, hundreds of experiments have shown that System 1 is what mostly drives our decision-making process. As Kahneman states, this is because System 1 “effortlessly originates impressions and feelings that are the main sources of the explicit beliefs and deliberate choices of System 2”. We make emotional and rash decisions without even realizing it, and then rationalize them to ourselves.

“If I look at the mass, I will never act. If I look at one, I will.” - Mother Theresa

Humans also tend to relate more to specific individuals rather than groups. We empathize more when a problem is humanized with details of a single victim - details like a story, a face, or a name. Notable economist Thomas Schelling established this notion as the Identifiable Victim Effect, stating that harm to an individual invokes, “anxiety and sentiment, guilt and awe, responsibility and religion, [but]…most of this awesomeness disappears when we deal with statistical death.” Although it would make more rational sense to be moved by a number of people, the emotional side of our brain, System 1, takes over. We see this demonstrated heavily in the media already, with advertisements and charity websites calling on one or two individuals to share their stories, in turn eliciting an emotional reaction in the viewer that drives them to donate.

In addition to learning about these psychological principles, I was able to do some user research by speaking with a couple of people who worked closely with the low-income community in Boston. They stressed the importance of long-term relationships, trust, and privacy. Many homeless and low-income women have been through great difficulties, and it’s not easy for them to open up or ask strangers for help. Women who live in shelters or on the streets value their privacy and safety over all else. After learning more about these users, I had to make a decision on how to approach the fact that many women might not want to reveal their face and name.

To find a balance of information that suits both business and user needs, research is invaluable. In the future, I hope to explore more about the inherent biases in exposing personal details and I would like to quantify these effects for further research. All in all, this project was vital in exposing some of the deep psychological background behind seemingly small design decisions in a human-facing app.

If you’re interested in learning more about Saloni’s research or have a similar project you’d like to talk about, please send us an email.