I’ve been a part of quite a few development efforts over the years and can’t help but notice that we tend to rely on a ubiquitous and alarming architectural anti-pattern: developing a “monolithic” codebase wherein all of the required logic is located within one ‘unit’ (a war, a jar, a single application, one repository). Consider this post a plea for us to collectively get away from this approach and to try something new.

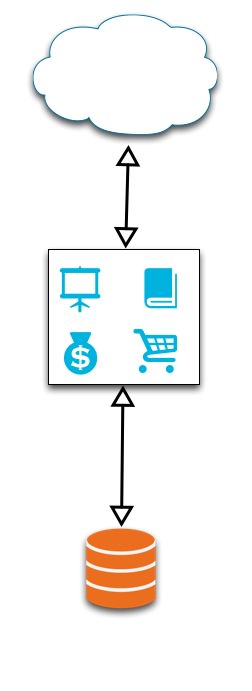

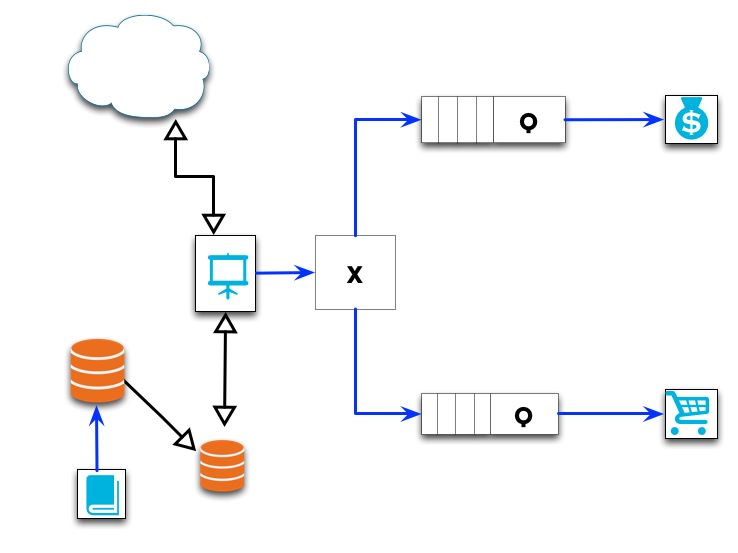

Consider this diagram:

It depicts an example of a simple e-commerce web application. The orange cylinder represents your database, the cloud is the mass of incoming requests via the internet, and the blue symbols represent the features of the application, enclosed within one monolithic bounded context (the black box).

The blue symbols each represent:

- Screen: Product Browsing (this is the view the customer sees)

- Catalog: Product curation and management (primary method for internal users to manage the application)

- Shopping Cart: The customer’s cart, containing any reserved inventory

- Money Bag: Order placement, processing, and history

This pattern is extraordinarily common for several reasons: it’s easy to conceptualize. Starting from a blank slate, a team can achieve Minimum Viable Product (MVP) quickly. All the code is in one convenient location. Setting up a dev environment is easy.

But that’s it.

The complexity of this architecture pattern will quickly become enormous, particularly once MVP is achieved. The development pace that was maintained during initial development will not continue, particularly once you start to attract users and grow your team. If there’s anything you take away from this post, it should be this: the monolithic architecture pattern will not scale efficiently.

The monolithic architecture pattern will not scale efficiently.

At this point you might be saying to yourself, “Wait a minute, what do you mean it doesn’t scale?! We can take our application code, place it on other machines, and throw them behind a load balancer. Or, if there’s contention on the database, we could institute a master/slave replication strategy or add some shared caching.” Yes, well, certainly you could — but that’s not exactly what I mean.

The term ‘scale’ has a larger definition than just the capability to handle additional users or process requests more frequently; it also refers to the capability of your team to operate efficiently on the code as it grows to meet user demand. The ability to add new features, fix bugs, or resolve technical debt becomes ever more difficult as the complexity of the code base increases — and will not scale at all if your code remains as one codebase. Hiring more developers or increasing your team size will not increase development time (cough Mythical Man Month cough), and in fact there may be a point where bringing someone new on to the team is a net negative on productivity. Developers will be stepping on each other’s toes, and more experienced folks will be teaching, answering questions, or explaining the codebase to less experienced devs.

This situation is not just limited to greenfield projects; what about the inevitable major refactoring of a portion of the application, let alone the whole thing? You’ll need to run several teams in parallel. One will will be working on the refactoring while a second team continues on with maintenance and developing new features on the established code base. Team one will need to continually keep their code up to date with the team two’s efforts to ensure nothing breaks. And thus the knot persists.

This scenario is, frankly, a nightmare. So how can this situation be avoided?

One solution is Service Oriented Architecture (SOA). The basic idea is to convert your application into a set of services which communicate with each other via a common language. These communications are usually done via a synchronous call, typically via HTTP, sending either XML or JSON data. Each service node is responsible for a certain set of actions and maintaining a subset of data. When an individual service needs data from, or needs to push data to be processed by another service, it communicates the need to the target via this common language (i.e. no direct method calls).

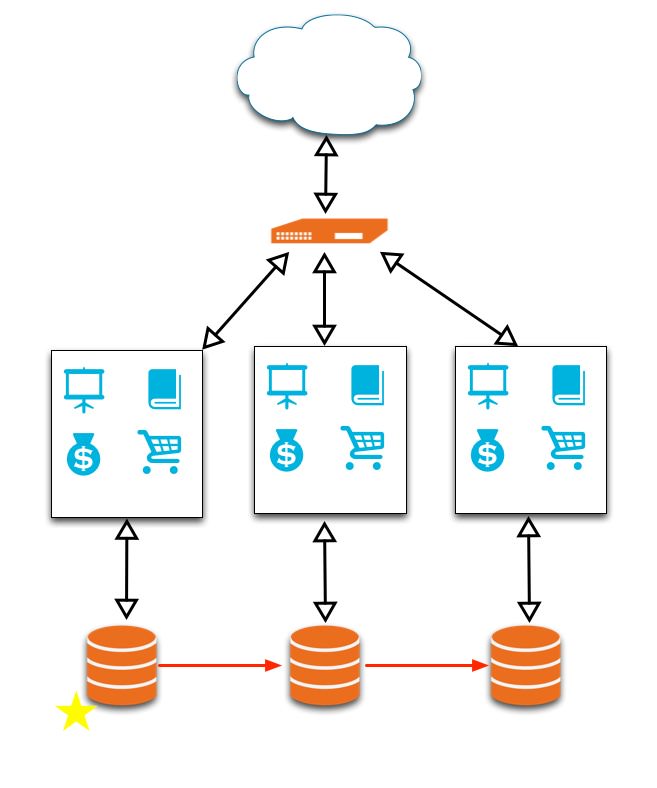

If we were to apply SOA to our previous e-commerce example, we may end up with a diagram that looks like this:

The diagram shows each of the features from the original design, but broken up such that each feature is now a distinct service, with its own data source and communication endpoint. We can see that the main interaction point for the client is through the product browsing feature, which ends up as the interface for sending and requesting data from the other services.

Breaking up (or decoupling) the single application into several several smaller services reduces overall complexity. Your developers will be able to quickly diagnose issues and add new features now that they’re working with disparate codebases with high degrees of responsibility for a certain set of tasks. In general, each service should operate more quickly; smaller code is faster code. Refactoring is now no longer something to be feared; because there is a defined communication format via the service calls, an individual service can be rewritten relatively quickly. We’ve also decoupled our application in terms of language; if a particular service is better suited to be written in Erlang, while Ruby is more appropriate for another, we can choose the right tool for the job. These productivity gains will lead to a long-term reduction in costs as your team will be able to operate more rapidly and efficiently.

Separation of concerns is a good thing.

I don’t think I can stress that enough, so let’s phrase it again: all code you write should have the goal of keeping complexity and inter-dependency to an absolute minimum.

All code you write should have the goal of keeping complexity and inter-dependency to an absolute minimum.

That said, SOA is not without its own set of problems. Having a web of interconnected services can also grow out of control. It becomes a chore to maintain the location of each service for each dependent service. Initiating an http connection is hardly trivial from a performance perspective, in addition to blocking the user request while we wait for a response from the service. Each service has to maintain which other service is responsible for the data it may need, or which services are responsible for storing or processing some set of data. There is an upfront cost in setting up the initial message design and structure, as well as extra infrastructure costs for configuring and administering the additional service nodes.

Some of you may be thinking “but wait, I could just use an Enterprise Service Bus!” and yes, you could, although it still has the synchronous problem. However, if you’re using an asynchronous ESB — well, you can probably stop reading this and get back to work.

Most importantly, this pattern requires an architect or a committee of folks whose job is to drive the SOA vision. Aside from general coding, this person / group of people should be involved with the initial decoupled design and must help drive the other developers forward with SOA principles (for example, knowing when to spin off a new service). They should also be tasked with creating tools to help keep the other developers productive, like creating tooling for mocking message requests and responses.

However, we can do better! By embracing the event-driven methodology of languages like NodeJs, Spring Integration, or Vert.x, but on a macro scale (although I strongly advocate for writing your individual services using an Event-driven pattern), we can achieve even greater performance and scalability.

This architecture pattern is called ‘Message Oriented (Decoupled) Architecture’ (MODA); I add the ‘Decoupled’ in order to highlight the importance of keeping responsibilities separated. It incorporates the disparate service oriented approach from SOA but with one major change: instead of servers communicating directly between each other synchronously, all communication takes the form of a Message which is placed on a Queue or Message Broker (software that directs messages across multiple queues), which are then consumed asynchronously by another service. For each communication, the services will take on the role of a Message Producer or a Message Consumer. These messages generally describe events that occur within your system, e.g. “User placed an order”, “User updated their address”, etc. MODA also grants us decoupling across three more facets:

- Time: Asynchronous messages do not block the Producer

- Location: Services only need to know the location of the Broker or Queue, and do not need to know or care about the location of other service nodes

- Cardinality: Services do not need to know the number of currently deployed nodes of a given service type (e.g. how many Order Processing service nodes are active).

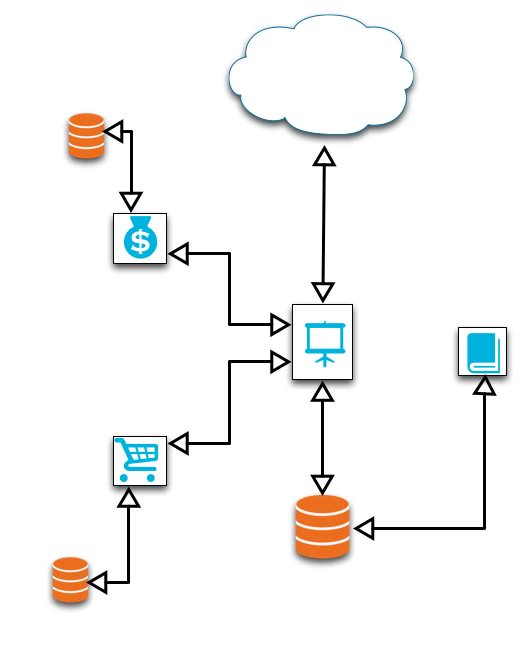

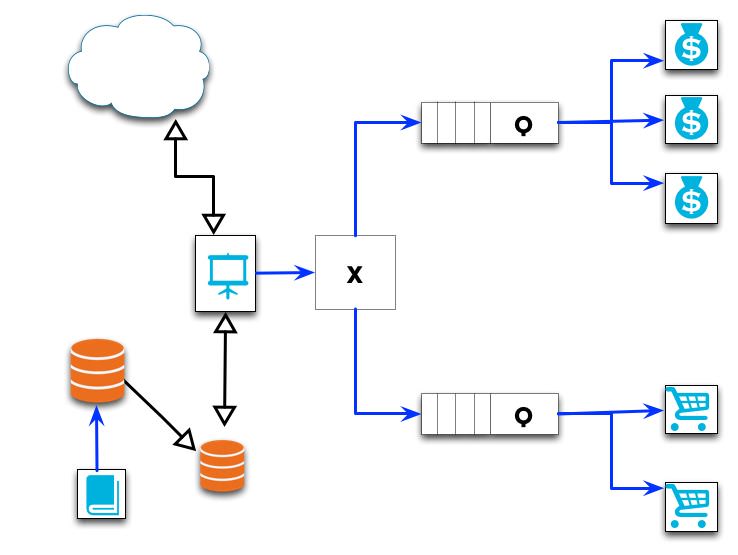

Below is a diagram of our previous example, but laid out in MODA format:

Here the blue lines represent message calls, the rectangles with a ‘Q’ represent Message Queues, and the box with an ‘X’ represents a Broker (which may be overkill for this example). Our internal users work with the Catalog service to make changes to which products are being sold. The changes they make are placed on a queue and saved asynchronously to a Master db, which is periodically replicated to a slave database(s) that back the Product Browsing application. As users browse the wares and add products to their cart, messages are placed on the queue for the Cart service (An aside: if one were to use Event Sourcing in the persistence store of the cart, this could be of excellent use to any internal data analysis). When Orders are placed, a message is placed on the Order Processing queue.

Consider what this means for a moment. Most of the traffic is going to be in the general browsing of your application, which is backed by a read-only database (and, perhaps, a cache). If you receive a spike in Order placement (which generally will take a bit of time to validate payment information, reserve inventory, etc) and were operating in a synchronous environment (either monolithic or SOA), each order placed would block the request thread while the processing completes. This has a direct impact on other users’ product browsing or additional order placement. Once the order is complete, the UI notifies the user that things were successful, we send a notification email, and resources are freed to handle another user.

But do we absolutely need to synchronously inform the user if the order was successful? In the MODA environment, any time an order is placed, a message with the relevant details is dropped on a queue, the UI displays a notification to the user of something akin to “thank you for placing an order with us, we will send you an email confirmation shortly,” and the main user entry point (product browsing) can resume handling user requests. Meanwhile, the Order processing nodes are picking off the messages from the queue as rapidly as they can, performing the relevant credit card information, reserving inventory, and firing off a success or severely apologetic failure email. Assume success, and ask for forgiveness later.

Note the use of the word ‘nodes’ in the previous paragraph. This is perhaps my favorite part of this pattern: we can programmatically monitor the performance of our queues and scale our nodes to meet current demand. Taking our running example, if we were to receive an unusual number of orders and the Order Placement queue was backing up, we could fire up additional Order processing nodes and latch them to the queue — all potentially without any additional configuration and with only a marginal impact on the end user. We continue to dump messages onto the Order queue and drain as we can. In this fashion we are scaling up only the affected portions of our application, on demand (although we’d probably want to have some finite maximum limit so we don’t run up a huge server bill if we suffer a DDOS).

One weak point of this pattern is the vulnerability of the Message Queue; we obviously do not want to lose any information, but what happens if the Queue cannot drain Messages fast enough and it crashes or suffers a system restart? Several Message Broker libraries can persist each message as they arrive; in the case of a crash, the Broker can be restarted with all Messages intact. Incidentally, I recommend RabbitMQ for its durability and ease-of-use, but there are several excellent alternatives. That said, the choice of Message Broker isn’t as important as actually following the MODA pattern, although I’ll hopefully eventually get to putting together post about using Message Brokers in practice.

I’ve skipped over several lower-level implementation details, each of which could use its own post. For example: how does one set up a dev environment when working with decoupled services? What sort of details should be in the message format? Does each message need the same details? Do I absolutely need all communication to be asynchronous? How does one begin converting their monolithic app to adhere to MODA?

Regardless of these details, I hope this post has provided some insight into how a Message Oriented Architecture can help scale your application.